Activities

Our Blogs

Morphine and driving

There is love. And there is longing. Both play out in social media as human confessions – sometimes evoking pity, on occasions a snigger, but mostly as a shout in the dark for help. A picture of the humble gulab jamun on facebook will have our NRI friends fawning over it. Now, that is longing. Love, in particular the romantic kind, on the other hand, gets us entangled in our passions and could be the fountainhead for the greatest joys and perennial problems. For when it fails, it appears that someway or other the world has turned it’s back on us. Yet it remains as a constant beneath the shifting experience of life.

Human aspirations change, but human nature does not. The Devadas of today might appear dapper with a 4G connection and skinny jeans, but he still croons for his lost love. And when he is done, he gets busy updating his relationship status to ‘complicated’ or ‘single’ depending on how he took rejection, with a few teardrops in his keyboard. No wonder Spinoza, one of the great rationalists of 17th century philosophy, observed ‘Desiderium ipsa essential hominis’ – desire is the very essence of man.

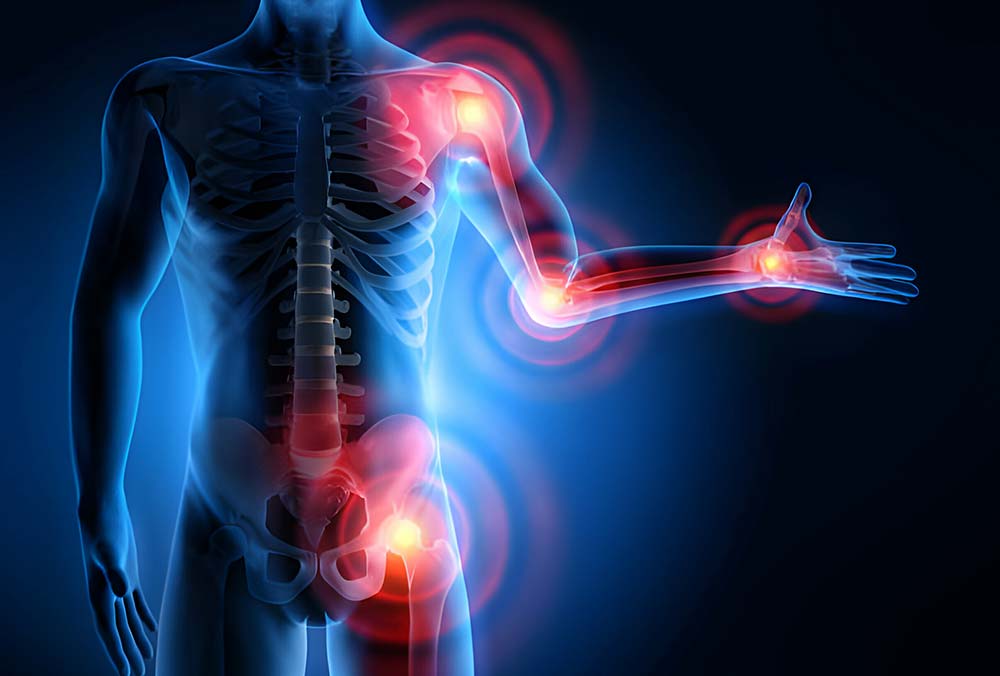

A basic feature of human experience is to feel soothed in the presence of loved ones and to feel distressed when left behind. Our languages reflect this experience in assigning physical pain words such as ‘hurt feelings or emotions’ to describe the experience of rejection. However, the notion that the pain associated with social rejection is similar to the pain experienced upon physical injury seems more metaphorical than real. Or, is it? If love and longing are human confessions, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a sort of divine revelation that measures brain activity by detecting changes associated with blood flow. Pain, the most primitive signal that ‘something is wrong,’ activates a certain brain region that is more concerned with the aversive quality of it. The same region is activated in the experience of pain associated with social separation or rejection. Associated with break-ups and heartaches, ‘singulate’ cortex would have been the appropriate moniker for the region, but the powers that be conspired to call it ‘cingulate.’

Though not as much as an inconsequential celebrity in dodgy satellite TV awards, a stubbed toe might still make one cry. It is in the cingulate cortex where this aversive quality is processed. It is also important to detect the sensory components of pain such as severity and location. This is done in the brain regions called the somatosensory cortex and insula. Researchers then had a different question. When rejection is powerfully elicited—by having people who recently experienced an unwanted break-up view a photograph of their ex-partner as they think about being rejected – do the areas that support the sensory components of physical pain too become active?

The bloodthirsty group now had to recruit subjects for their study. To understand true failed love they could have looked at wedding albums. Every wedding album the world over faithfully conveys that sinking feeling. Instead, they put up posters in Manhattan and scoured facebook and Craig’s list. Forty individuals (21 females) who experienced an unwanted romantic relationship break-up within the past 6 months, and indicated that thinking about their break-up experience led them to feel rejected were studied.

There were two different tasks for the participants. The social pain task involved looking at a headshot photograph of the ex-partner and a same-gendered friend with whom they shared a positive experience, with cue phrases appearing beneath the photographs that directed them to focus on a specific experience they shared with each person. The physical pain task involved applying heat to the forearm at two different temperatures, one painful and one non-painful. fMRI scans acquired during these counter-balancing tasks clearly demonstrated the overlap between social rejection and physical pain. These results give new meaning to the idea that rejection ‘hurts.’ They demonstrate that rejection and physical pain are similar not only in that they are both distressing, they share a common pattern of activations in the brain as well.

The underlying commonalities between physical and social pain unearths new perspectives on issues such as why physical and social pain respond favourably to social support, and why it ‘hurts’ to lose someone we love. It also offers new insight into the association between rejection experiences and pain conditions such as fibromyalgia and somatoform disorders. Future research might tell us whether observing someone else experiencing intense social pain also recruits the same pain processing regions in the brain. And importantly, whether having the expectation that one will be rejected in the future activates the brain regions the same way as physical pain expectations do. Therein lies a business opportunity for the medical devices industry to be in direct competition with the ‘Agony Aunt’ columnists. Mind you, not long ago heroin was marketed by the drug company Bayer as a safe, non-addicting treatment for tuberculosis, among other things.

Prev

Prev